Last updated: 29 May 2025

Contents

Introduction

Since the General Election, the topic of housing, more specifically home building and the planning system within which the industry operates, has captured the attention of politicians, media and the general public more widely.

While the changes to the planning system are welcome moves, there remain many constraints to housing supply and demand which have the ability to hinder housing delivery, such that the ambitious 1.5 million homes target may not be met by the time the next election rolls around.

The Government has stated many times a desire to improve home ownership, but so far, there has been little announced that will see these promises translate into a reality for many people.

Considerable attention needs to be paid to the combination of barriers facing aspiring homeowners. As this analysis shows, the number of households and individuals that can currently access home ownership is significantly below the number that could have at most points in the last 25 years.

History of home buying schemes

For the best part of 60 years, government initiatives aimed at supporting more people into home ownership have featured in the housing market.

Since the 2000s, these have mostly been varying iterations of equity loan schemes, funded by the government, or by a mix of the government and participating developers, covering a percentage (typically 20-50%) of the property’s value. These schemes make home ownership more accessible by lowering the value of the mortgage required for those households that can’t otherwise raise a mortgage to cover the full price, and by lowering initial mortgage costs.

The most recent of these, the Help to Buy: Equity Loan Scheme, could be considered the most successful. Over its decade lifespan, almost 400,000 properties were purchased under the scheme, 85% of which were bought by first time buyers.

Challenges facing first-time buyers

While home ownership has been England’s largest housing tenure since the mid-1970s, levels peaked at 71% in 2003 and have fallen since, now sitting at just under 65%.

Previous research from the Home Builders Federation (HBF) found FTBs are facing numerous challenges relating to house prices, mortgage costs and deposits. For example, for first-time buyers, the average price to income ratio in England is 10. This rises to over 12 in the South East, South West and East of England, and is over 16 in London.

With regards to mortgages, for the average first-time buyer, the monthly mortgage payment was 47% of net salary in 2004 and 2014. As of 2024, this has risen by 20 percentage points to 67%. While this may not be surprising given the economic climate of the past few years, it is nevertheless a significant and for many, insurmountable.

The growing size of deposits is also a barrier. The average first-time buyers in England would have to save 50% of their discretionary income for nine years to save the necessary deposit. This rises to 13+ years for those looking to buy in the South East and London.

After setting aside rent and bills, first-time buyers in England are typically facing a deposit that is more than 400% of their remaining income.

How the market of potential buyers has changed

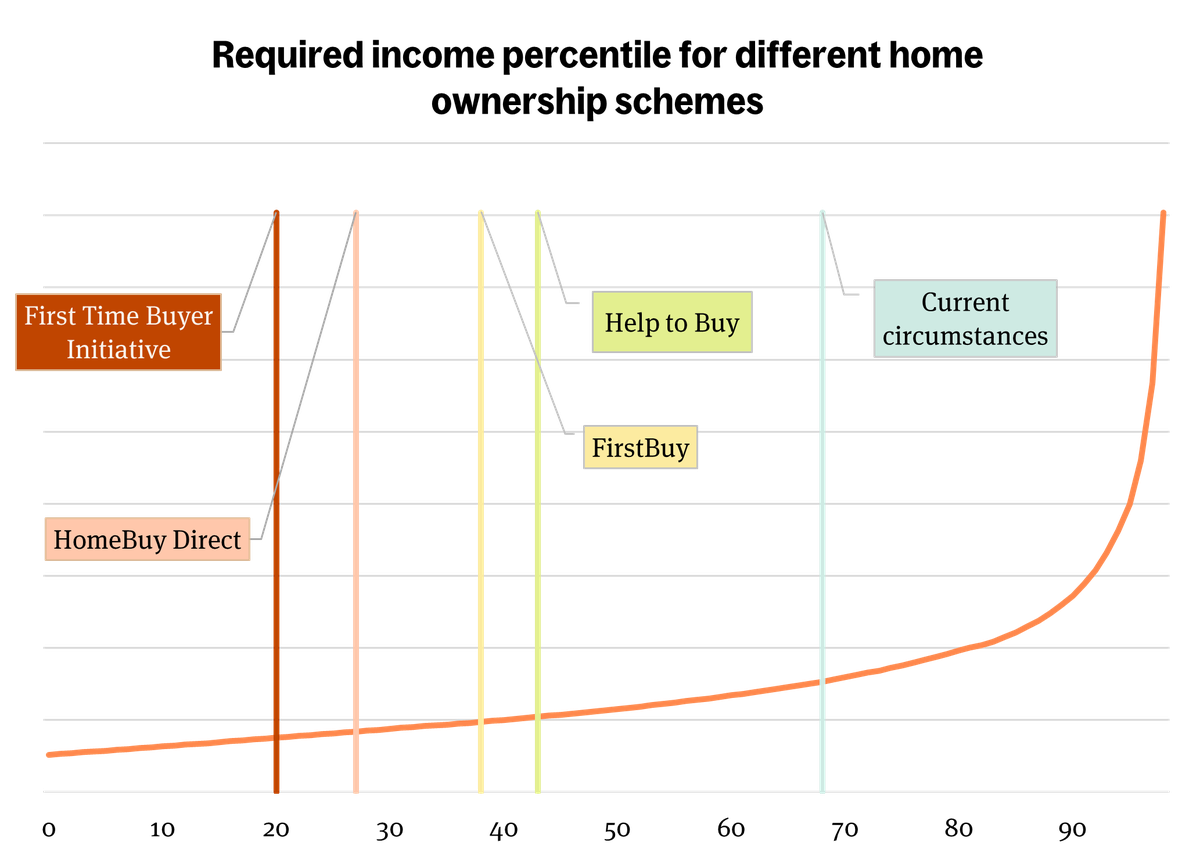

All of these barriers significantly reduce the number of people able to get their foot on the first rung of the property ladder. Under the various schemes explored below, home ownership was a realistic achievement for people not just on the highest salaries or with family money.

First Time Buyer Initiative

The First Time Buyer Initiative (FTBI) was introduced in 2005 under the Blair government. The scheme aimed to assist social tenants, key workers and other first-time buyers who could not afford to buy in their local market.

Under the FTBI, the Government provided a loan of up to 50% of the property price, with the remaining 50% made up of a deposit of at least 5% and a mortgage. The loan was interest-free for three years, with buyers paying fees to government based on its contribution after this (1% after three years, 2% after four years and 3% thereafter). The buyer then repaid the assistance to government when the property was sold, i.e., if the government contribution was 50%, then the seller would repay 50% of the total value at the time of sale.

The scheme opened up home ownership to a significant proportion of the population.

In 2005, the average new build property price was £197,294. Under the FTBI this was broken down as:

- Government loan (50%) = £98,647

- Deposit (5%) = £9,864

- Remaining mortgage (45%) = £88,782

Assuming that lenders would provide a mortgage of 4.5 times household income, and assuming that a potential buying household is made up of two earners, a household would need a combined income of £19,729, or an average of £9,864 per person in order to secure the necessary lending

As a result, in 2005 those within the 21st percentile of earners were able to buy a property under the FTBI.

The FTBI had a household income cap of £60,000 – on average £30,000 per person. This restricted eligibility to use the scheme at the 79th percentile of earners, as it was assumed that these higher earners would not need government assistance to get onto the property ladder.

In other words, 58% of the population could have potentially purchased a property under the FTBI.

HomeBuy Direct

HomeBuy Direct was announced in 2008 and was open for a year from 2009 to 2010.

The scheme provided a 30% equity loan for first-time buyers purchasing a new build co-funded by the government and the developer. 10,000 homes were purchased during the scheme’s short lifespan. The scheme operated similarly to the FTBI in terms of interest and repayment terms.

For a first-time buyer couple purchasing in 2009, the average new build house price was £190,535 and the costs were broken down as follows:

- Loan (30%) = £57,160

- Deposit (5%) = £9,530

- Remaining mortgage (65%) = £123,850

- Household income = £27,521 or £13,760 per person

This placed the required income at the 28th percentile.

FirstBuy

FirstBuy was announced in 2011 and was the precursor to Help to Buy, with 16,500 homes purchased using the scheme.

The format of FirstBuy was similar to HomeBuy Direct but with a 20% loan, co-funded by the government and participating developers.

The costs were broken down as follows:

- New build house price = £203,959

- Loan (20%) = £40,791

- Deposit (5%) = £10,196

- Mortgage (75%) = £152,969

- Household income = £33,993 or £16,996 per person

This placed the required individual income at the 39th percentile.

Help to Buy

The Help to Buy Scheme is probably the most well-known of the government-backed equity loan schemes and, as discussed earlier in this report, is the most successful.

Help to Buy provided a 20% loan (40% in London) towards the deposit of properties purchased using the scheme, with the buyers providing a minimum 5% deposit, with an initial maximum purchase price of £600,000 across England. The loan was interest-free for five years.

Announced at the 2013 Budget, the scheme was established with the aim of improving both home building levels and to increase the supply of low-deposit mortgages for creditworthy households. At the time, the Global Financial Crisis had seen most lenders reduce their Loan-to-Value (LTV) offerings to 85% on houses and 80% on flats. As a result, confidence dipped and investment in new housing schemes dropped significantly.

Help to Buy successfully addressed these issues, with HBF’s 2024 Road to Redemption report finding that the scheme:

- Supported almost 400,000 buyers to buy an energy efficient new build home, including just under a third of a million first-time buyer households;

- Created an unparalleled period of housing supply growth following investment from builders who were given confidence over future demand for new homes;

- Has so far generated a net return on investment of £718m for the Exchequer to date (+9% against original value of loans) in addition to more £220m in interest payments;

- Is likely to generate a positive return on investment of more than £2bn once the performance of loans and interest income has been accounted for.

Unlike previous equity loan schemes, for the first eight years Help to Buy was not limited to first-time buyers and there was no income cap. The eligibility criteria for the scheme was then made more restrictive scheme, with the scheme then limited to first-time buyers and with regional price caps in place ranging from £186,100 in the North East to £600,000 in London.

The first stage of the Help to Buy scheme, which ran from 2013 to 2021, saw over 328,000 purchases made, 82% of which were by first-time buyers.

While Help to Buy was criticised for not implementing an income cap, as many of the past schemes did, due to concerns that it would be used by those who didn’t actually need assistance, the data on Help to Buy demonstrates that this was not the case in reality.

As the graph below demonstrates, the median household income for all users of Help to Buy was consistently below £60,000, only going above this level for non-first-time buyer applicants toward the end of the first stage of the scheme.

For first-time buyers only, assuming that most households had two applicants contributing towards the income, the average individual income shows the scheme was reaching those who would otherwise likely be pushed out of home ownership.

At the time of the closure of the first stage of the scheme (2001), the average new build price was £302,916. Users of the scheme would receive a loan of £60,583 and provide a deposit of £15,145. This would leave them needing a mortgage of £227,187. A two-person household would therefore require an average income of £25,250 per person.

For this, an individual would need to be in the 44th income percentile – meaning more than half of the population were eligible to purchase a property.

Current requirements

The closure of the scheme with no replacement has since seen a significant wall placed between home ownership and much of the population.

At the end of 2023, the average new build home was priced at £356,602. With a 95% LTV mortgage, a household would need to raise a mortgage of £336,087, requiring an income of £37,641 per person for a two-person household.

This places an individual applicant in the 69th income percentile, effectively pricing out an additional 25% of the population that could’ve bought a property using Help to Buy.

Proposed scheme

HBF is urging the Government to consider a replacement equity loan scheme for first-time buyers which would:

- boost first-time buyers’ deposits, giving them access to new build mortgages which are priced more affordably

- see developers paying a fee similar to the ‘commercial fee’ payable by mortgage lenders for access to the Mortgage Guarantee Scheme

- involve developers covering a portion of the upfront investment in the form of a fee that would see HMG retain the full equity share.

Under this proposed scheme, FTBs would require a 5% deposit. This would be matched in the form of a 15% equity loan from Government, which would include a developer fee from the participating developer, equivalent to 1% of the sales price.

As a result, home buyers would gain access to a greater range of mortgage deals at far lower rates. 80% Loan to Value (LTV) mortgages are priced significantly cheaper than those above this level because of mortgage regulations governing capital requirements on LTV lending and risk weightings applied to portions of lending above 80%.

By providing a government equity loan of 15% and reducing the LTV to 80%, buyers are more likely to benefit by falling below 4.5x Loan-to-Income ratios and thus, again, having access to more mortgage deals and more affordable monthly repayments.

When the equity loan is paid off, Government would receive 15% of the value of the property despite the net upfront contribution having been 14% of the property value at origination. This is assuming that after three or five years, before interest is payable, the homeowner remortgages and repays the equity loan. This is the typical experience with Help to Buy. Because the developer will not retain an equity stake, house price inflation benefits would be taken only by the homeowner and the Exchequer.

Under previous schemes, the required 15% developer contribution was far above what many home builders could reasonably afford, with the exception of large national developers. HBF’s proposed scheme does not require any additional investment from Government but the 1% developer contribution ensures that smaller builders can also access the scheme.